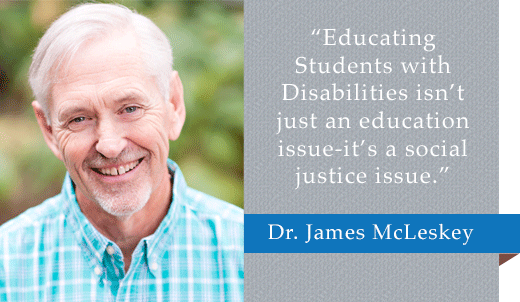

Dr. James McLeskey

Specific interests steer some researchers while they are in college. Professors in graduate school heavily influence others. Family members also push individuals in certain directions. However, an impersonal, steel Quonset hut behind a vocational school forged James McLeskey’s academic identity.

The architectural wonder did not have air conditioning. It did not even have a functional bathroom—students were forced to travel to the main building each time they needed to use the restroom. What the Quonset hut did have was a group of disabled students segregated from the rest of the school population. James remembers his bewilderment the first time he walked into the hut: “Wow,” he recalls. “I didn’t know we treated people this way.” The Quonset hut transformed James from a young man with an uncertain professional path into a staunch advocate for students with disabilities. Advocacy is the concept that weaves throughout James’s career.

James did not start out with the hut in mind—or even with education as a career goal. He began college aiming to become a counselor, so he majored in psychology and then pursued graduate work in counseling. After completing his master’s degree, James accepted a job teaching students with intellectual disabilities at the vocational school—the site of the Quonset hut. James spent several difficult years laboring to include his students in mainstream educational and social activities, and he enjoyed moderate success. Several of his students played varsity basketball and football, and many were included in general education classrooms. James soon decided that he wanted more leverage so that he could influence a wider range of students. He had already become an advocate; he just needed a bigger platform.

While pursuing his doctorate at Georgia State University, James became even more convinced of the necessity of being an advocate for students with disabilities, and he focused his efforts on inclusion and developing quality teachers and leaders. “Teachers ultimately make it happen every day, but principals provide a setting where effective inclusive schools can occur,” he says. He believes that CEEDAR Center professionals can deliver assistance in improving teacher and leader preparation programs, which will equip leaders with the necessary tools for creating inclusive schools with positive learning environments. He also envisions CEEDAR Center staff members helping general education teachers to better understand how to educate students with disabilities in their classrooms.

James has mixed but optimistic feelings about the state of special education today. He laments that many students are still in their own Quonset huts. He acknowledges that these may not be steel buildings out back; they could be separate wings or halls, but exclusion still exists. However, he is hopeful about the fact that 80% of students with disabilities spend a significant amount of time in general education classrooms. Like a true advocate, though, James’s work is never finished.

While discussing his legacy, James is uneasy. He does not believe in striving for a legacy. He believes that real change happens in the accumulation of day-to-day victories. He admits that throughout his life, he has seen solid successes and definite failures. Ultimately, when he retires, he hopes that he will have been a Quonset-hut demolisher. He hopes that fewer students with disabilities will be excluded and that more teachers and leaders will become well-equipped to teach these students.

Like many of our CEEDAR Center team members, James is a spirited basketball fan. He is confident that the Gators will win it all this year (a conclusion shared by many on our team). What he likes about the team is how well-coached they are. Growing up in the Bob Knight era, he appreciates how a talented coach can take a group of players and form a positive team synergy. He equates a good principal with a good coach. He wants to help develop in our education system some Billy Donovans who can help teachers work well together to improve student outcomes.

Aside from basketball and academic pursuits, James enjoys an active lifestyle. He and his wife are planning a week-long bike ride through Italy this summer. This culinary cycle tour from Cremona to Bologna will include beautiful scenery and delectable Italian delicacies. (He is making the rest of the CEEDAR Center staff very jealous.) James is also a huge Rolling Stones fan. In fact, a walk straight past his “Dr. James McLeskey” office sign will often lead to the sounds of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. James is amazed that a band plagued by so many personal issues has been successful for such a long time. Although he does not want Mick Jagger’s lifestyle, he claims that if he could choose any other skill set, he would love to be a great musician. “Time is on Your Side,” James. You could be the first special education professor to have books, articles, and Billboard Top 10 hits on your CV.

This website was produced under U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, Award No. H325A220002. David Guardino serves as the project officer. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Education. No official endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any product, commodity, service, or enterprise mentioned in this website is intended or should be inferred.

This website was produced under U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, Award No. H325A220002. David Guardino serves as the project officer. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Education. No official endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any product, commodity, service, or enterprise mentioned in this website is intended or should be inferred.

If you spend just a few minutes with Maury McInerney, two things will be clear. First, he passionately believes in the importance of translating the theoretical to the practical. Second, he is passionate about being someone who does this on a grand scale.

If you spend just a few minutes with Maury McInerney, two things will be clear. First, he passionately believes in the importance of translating the theoretical to the practical. Second, he is passionate about being someone who does this on a grand scale. Dr. Suzanne Robinson is driven by an intense curiosity. Although she recalls teaching her dolls in a mock-classroom in her basement at age 4, she wasn’t always sure that research was going to be her life’s work. Her passion for educating teachers developed out of curiosity. While in college, sociology and anthropology stoked her interest. Those fields explore the depths of the human experience. They attempt to answer the “why” behind the status quo. Sometime later, Suzanne was working with a child who was struggling to read. At the time, she didn’t realize that the student likely had a learning disability, but her mind immediately jumped to the “why?”. However, even behind the “why?” the child was struggling was the bigger question of “how?”-how could she make a difference? Special Education research exists at the intersection between “why” and “how”. Her intense curiosity of why people think the way they do led her to want to understand how she could help students with learning disabilities and how she could help the teachers who teach those students.

Dr. Suzanne Robinson is driven by an intense curiosity. Although she recalls teaching her dolls in a mock-classroom in her basement at age 4, she wasn’t always sure that research was going to be her life’s work. Her passion for educating teachers developed out of curiosity. While in college, sociology and anthropology stoked her interest. Those fields explore the depths of the human experience. They attempt to answer the “why” behind the status quo. Sometime later, Suzanne was working with a child who was struggling to read. At the time, she didn’t realize that the student likely had a learning disability, but her mind immediately jumped to the “why?”. However, even behind the “why?” the child was struggling was the bigger question of “how?”-how could she make a difference? Special Education research exists at the intersection between “why” and “how”. Her intense curiosity of why people think the way they do led her to want to understand how she could help students with learning disabilities and how she could help the teachers who teach those students.